TechResort Alumnus, Sean, is asking for our politicians to take digital inclusion seriously…

The General Election has been set for Thursday 4th July. It’s absolutely vital that all parties standing, and the next Government, take the issue of digital exclusion seriously.

The 2023 Lloyds Bank UK Consumer Digital Index puts the number of people who have ‘very low’ or ‘low’ digital skills at over 18 million people – or over a third of the population.

Here are 5 reasons the next Government must take steps to better support digital inclusion services.

1) Exclusion Drives Poverty

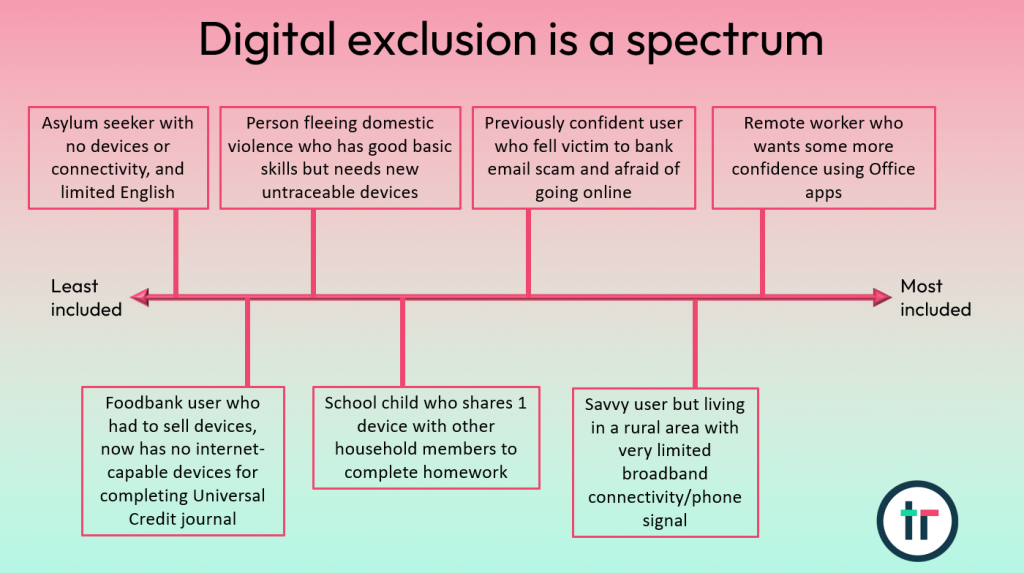

Digital exclusion should not be seen solely as an issue relating to older people preferring traditional methods of interacting with the world, somebody being hesitant to learn by choice, or merely a symptom of other forms of poverty.

Instead, it must be viewed through the lens of being deeply intertwined with other forms of poverty and exclusion. A lack of digital access and confidence contributes to, and exacerbates, these other issues – whether it be unemployment, financial uncertainty, health worries, food or fuel poverty, or social isolation.

An accelerated move to ‘online-first’ (or, as often ends up happening, ‘online-only’) services during the pandemic, combined with ongoing cuts to the budgets of many support services – mean that accessing help and improving somebody’s socio-economic situation becomes significantly easier if they are digitally included.

This perpetuation is a vicious cycle – the longer somebody can’t get online, the longer they will be unable to improve their circumstances and remain in poverty. A 2023 Centre for Social Justice report, ‘Left Out’, states that digitally excluded consumers could pay 25% more for essential goods and services – without access to tools such as price comparison websites or online-only discounts.

As household budgets become increasingly squeezed, people are unable to find the money for devices. A basic smartphone that would be just about enough for day-to-day usage (but still likely a struggle for some tasks which would benefit from more processing power, or a larger screen), plus a reasonable data allowance, would still cost around £25/month. There are many people who simply do not have this capacity and so remain offline.

Sadly, I’ve also seen many people attend digital drop-in sessions who have had no choice but, out of desperation, have had to sell their devices in order to pay the bills for that week. This has then put them at a significant disadvantage going forward and they have entered the vicious cycle. Citizens Advice estimate that 1 million people cancelled their broadband access between 2022 and 2023 as a direct result of cost of living pressures; with those on Universal Credit six times more likely to have disconnected.

It is only thanks to the work of the third sector – with schemes such as TechResort’s device donation scheme, and the National Databank – that people have been able to get back online. Accessing this support, however, remains a postcode lottery.

Device and connectivity access is just one strand of inclusion. Simply handing somebody a device is not digital inclusion. Ensuring people have the skills, and can get help, creates enhanced digital confidence. This requires a community presence, which leads to the next point…

2) Good inclusion can provide holistic help

In my experience of running thousands of hours of digital drop-in sessions across a range of community venues – nobody ever describes themselves as “digitally excluded”. There’s a semantic debate to be had about the term, certainly – but it underlines the fact that people are rarely excluded by choice.

I’ve had countless occasions where somebody has approached us at a digital drop-in session with a small digital problem. As we get chatting, it’s extremely common to hear people open up about other issues they may be facing, and how digital exclusion hampers their ability to get it done.

Consider the digital skills and access required to, for example: update a Universal Credit journal; send off a job application; attend a job interview over video call; send bank statements to a housing officer or landlord; manage finances with online banking; submit a meter reading – the list goes on. For everyday users, tasks such as creating and using an email account, logging in with multi-factor authentication, or filling out forms, may seem trivial. For nervous or first-time users, these pose real barriers.

When people attend a TechResort drop-in, they can then be referred or signposted to more specialised partner organisations to get proper help – and TechResort are working on a process to better join up the support sector in East Sussex.

Having a visible presence in community venues where people already access help – or near the centre of a busy town – means visitors have one fewer barrier to finding digital help – and when people need it – other forms of help. A classroom-based setting might work for some, but likely not those the furthest away from support.

So far in 2024, TechResort have run 90 digital drop-in sessions – and I’d urge any local decision makers to attend one, to inform their understanding of what digital exclusion (and good inclusion practice) is.

Asking for help is embarrassing, and some support services require digitally booking an appointment online or over the phone, or may inadvertently create an uncomfortable environment for people to ask for additional help.

Yet, despite the value of digital inclusion support as an entry point for further support – funding provision is extremely scarce, both in the third and public sector.

Many local authorities are not able to provide any digital inclusion services themselves – and when they do, there may be limitations on access, and are often thin on personnel. Equally, volunteers in the charitable sector are likely to be stretched to capacity or lacking in digital confidence themselves.

Accessing unrestricted funding in the third sector is extremely difficult for many organisations – particularly those at a grassroots level, embedded in, and led by, their communities. These groups do not have the resources to spend time fundraising and dealing with reporting requirements without taking valuable time away from delivery.

3) Poor workplace skills harms the economy

The upcoming election campaigns will no doubt cast a focus on the economy – yet one key issue facing businesses, that many won’t be fully aware of – is the lack of digital skills in the workforce.

FutureDotNow state that over 21 million working age adults can’t complete all essential digital workplace tasks. For businesses who do not invest in proper digital training for their staff, this can lead to decreased productivity, innovation, and staff morale; all of which can have severe knock-on impacts.

On a macro level, FutureDotNow go on to estimate that between 2018 to 2028, the lack of digital skills in the UK’s workforce risks losing £145 billion in cumulative GDP growth.

A 2019 report commissioned by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport found that overall, roles requiring digital skills pay 29% (or £8,300 a year) more than role which do not – and that digital skills are required in over 82% of all jobs advertised online. The conclusion is simple – people without digital skills will earn less and have less secure income.

Making investments in a range of digital skills, from basic to advanced, and at all age ranges – will help the economy thrive.

4) Getting people online helps the NHS

Much like the economy, having a decisive plan for the NHS is seen as a vote-winner. Digital inclusion can play its part in helping the NHS, too.

As the health service faces growing pressure, there is potential to reduce some of the burden on face-to-face services by providing digital support. There already are good online self-serve options for ordering repeat prescriptions, booking appointments, and getting reliable and trusted information about how to treat minor conditions at home.

The NHS website states that in June 2022 alone, the app enabled 1.8 million repeat prescriptions to be made, and 130,000 GP appointments to be booked. This helps free up staff time and is more convenient for users.

However, getting started with the app – for the estimated 18 million people with low digital skills – can be a daunting experience. The Good Things Foundation estimate 39% of the UK adult population are not yet registered on the NHS App. It involves handing over personal details to an app and some fiddly steps such as face or ID verification, which leaves people hesitant to get started. Without community-based digital support to help people over these hurdles, take-up is at risk of stalling.

Similar digital access or skill barriers will also hamper other cost-saving measures, such as GP appointments which take place over video call.

A lack of digital confidence drives people back to face-to-face services when there are more efficient routes available. The Centre for Economics and Business Research estimated savings of up to £899 million by 2032 from reduced GP appointments.

5) Less democratic participation for those excluded

Both registering to vote, and applying for valid photo ID (now needed for voting at polling stations) – are digital-first processes. This form of everyday digital exclusion has been covered in a previous TechResort blog post – read it here.

Another form of democratic exclusion is that people who are not confident digital users may not be able to find and stay up to date with reliable sources of current affairs information online, or may not be able to identify fake news.

With the rise of AI ‘deepfake’ technology making completely fake articles, pictures, audio, and video seem plausible at a quick first glance, the regulation of this will pose a challenge for an incoming Government. As this BBC News article highlights – deepfakes have already caused problems, and the problem will grow as the technology develops and is able to produce increasingly realistic content.

Enabling voters to become digitally savvy users, who can identify both fake content and reliable sources, must play a large part in tackling this challenge.

To wrap up…

Inaction from Central Government over the past decade has worsened exclusion – the last Digital Inclusion Strategy was in 2014. The landscape has changed significantly since then, in part due to technology becoming far more widely adopted, and in part due to the pandemic accelerating changes.

An incoming Government could take suggestions from a recent House of Lords report, such as establishing a cross-government digital exclusion unit to ensure digital inclusion is actively embedded across in key policy areas. The report also praised community-based interventions – including those who do not offer formal qualifications – and recommended the Government work to ensure these organisations (such as TechResort) are not prevented from accessing sufficient resources.

To ignore the link between digital exclusion and other forms of poverty, worsened by the ongoing cost-of-living crisis, would be naïve. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation state more than 1 in 5 (14.4 million) people in the UK, were in poverty in 2021-22. The impact is significantly harsher on people with disabilities and from minoritised ethnicities. There are complex, deep-rooted, systemic issues in society that also need long-term fixes.

These issues are better tackled when people are better connected.